When an electric current flows through a conductor, it produces a magnetic field around it. This fundamental idea, confirmed by Oersted’s experiment, forms the foundation of electromagnetism.

One of the simplest systems for studying this phenomenon is a long straight current-carrying wire. Understanding the magnetic field around such a conductor is vital for analysing electric circuits, power transmission lines, and many electromagnetic devices.

Magnetic Field Due to a Long Straight Current-Carrying Conductor

Introduction

A long straight conductor carrying a steady current generates circular magnetic field lines around it. These field lines form concentric circles centered on the wire. The direction of the magnetic field depends on the direction of the current and is determined using the Right-Hand Thumb Rule.

This situation is idealised because we consider the wire “long,” meaning its length is much greater than the distance from the observation point. This assumption ensures that the field is symmetrical and can be easily described mathematically.

Right-Hand Thumb Rule

To determine the direction of the magnetic field around a straight conductor:

Hold the conductor in your right hand.

Place the thumb in the direction of the current.

Then the curled fingers around the conductor show the direction of magnetic field lines.

If the current flows upward, the magnetic field circulates anticlockwise around the wire. If it flows downward, the field circulates clockwise.

This rule helps visualise the orientation of magnetic lines of force around the wire.

Derivation Using Biot–Savart Law

The magnitude of the magnetic field at a distance ‘r’ from a long straight conductor carrying current ‘I’ can be derived using the Biot–Savart Law, which states: dB = µ0 / 4π . I dl sinΦ / r2

For a long straight wire, every small segment of the wire contributes to the magnetic field at the observation point.

By integrating over the entire infinite length of the wire, we get:

B = µ0I / 2πr

Here,

( B ) = magnetic field

(µ0) = permeability of free space (4π x 10-7) T·m/A )

( I ) = current in the wire

( r ) = perpendicular distance from the conductor

Key Observations:

The magnetic field is directly proportional to the current: More current produces a stronger field.

The magnetic field is inversely proportional to the distance: The farther we move from the wire, the weaker the magnetic field becomes.

The field is always perpendicular to the radius vector and tangent to the circular field lines.

Magnetic Field Pattern

The magnetic field lines around a straight current-carrying conductor:

Are circular and concentric.

Do not intersect each other.

Become denser near the wire (indicating stronger field).

Spread out as distance increases.

The pattern demonstrates that the magnetic field is strongest near the conductor and gradually weakens as we move away.

Dependence on Direction of Current

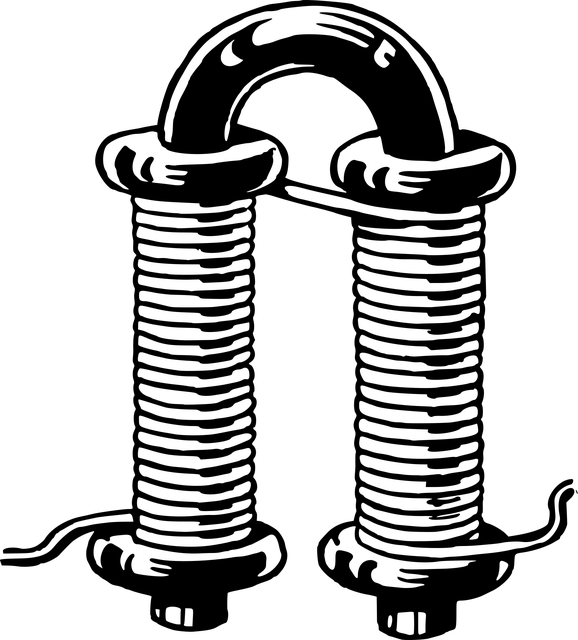

The direction of magnetic field changes when the direction of current changes. This phenomenon is vital in devices like:

Electromagnets

Solenoids

Electric motors

Induction coils

By controlling the direction of current, we can manipulate the magnetic field produced.